Why are we still calling it 'colonial'?

[TIL #19] Thoughts on feeling the icy fingers of colonial spectres around my neck

The guy wore a beard and hair so neat that they could have been made of shiny plastic, a fixed Lego set that no wind could ever shake. In jeans and a tee-shirt intended to reveal that he exercised a lot, he kept juggling with a couple of smartphones, texting on one, scrolling on the second device in between messages. He suggested that i should go upstairs: the sofa would be a perfect place to read and write, more comfortable than the chair and the small table. He also offered to refill the filter and the ice bowl to allow me to make more ice-coffee.

The ground floor of the café was in my eyes already quite a welcoming respite from the heat and a few fat drops of rain. A large mirror behind half-open wooden panels and a small pool full of restless fish made the room deeper. I also liked the small tables made out of old pedal-powered sewing machines. But out of curiosity, i climbed the stairs.

I immediately felt under the charm of a refined space that combined white walls adorned with pictures of days of old, a high ceiling of dark wood with slowly moving fans, a grand piano and a number of unidentified ancient objects of craft that mysteriously contributed to the refinement of the atmosphere. I did not sit on the sofa, instead i opted for a chair on an inner loggia and sat by the bas-relief of a smiling dragon. This was no less than a slice of heaven. I read, I wrote — it was a perfect moment. I was feeling like i almost belonged there: slightly out of this world and right where i was meant to be.

The town of Galle Fort is described in travel guidebooks and blogs as a ‘captivating destination where colonial charm meets modern allure.’ Now, ‘colonial architecture’ can be defined as « a hybrid architectural style that arose as colonists combined architectural styles from their country of origin with design characteristics of the settled country ». The term is used to refer to buildings erected during the times when the Portuguese, the Dutch and finally the English occupied and exploited the island of Sri Lanka. But these constructions have evolved and now serve very different functions than originally. Take the Old Dutch Hospital in Colombo, a couple of elegant courtyards surrounded by red-tiled buildings with yellow walls punctuated by wooden shutters: beautifully restored, it now houses shops, cafés and restaurants, and has turned into a cool spot for a cool drink and a bit of people-watching — the morgue of the occupiers’ hospital is now a pop-up concept store.

In most cases, owners are now local families (possibly descendants of the colonists). ‘We’ve got six houses’ my ice-coffee host had replied with pride when i congratulated him on the exquisiteness of his café.

Why then should we still have to call it ‘colonial’? Isn’t it time to name these beautiful renovated spaces ‘decolonised architecture’? It is important to preserve historical buildings. And - hey! - a lovely place to jot down notes while sipping a cocktail, that matters too. But colonisation is a bloody process of exploitation that should in no way be celebrated, and i am saddened to see that ‘c-word’ associated with the beautiful places now dedicated to leisure, conversation and relaxation. It may seem a small point when Sri Lanka sure has a fair share of heavy issues to deal with. There are more layers of exploitation and division in society than a name for an architectural style can say. Yet, words matter: we should speak of colonialism as an ugly and horrendous thing. We should acknowledge that times have changed: theses buildings are not a token of colonial charm, they are magnificently decolonised.

I’m aware that i’m giving myself the role of the person who stands on strong moral grounds or that even the benevolent traveller that i’m making myself to be speaks from a position of privilege. But here’s a small incident i witnessed in Galle Fort. I was looking for a book in a beautiful shop set in a colonial decolonised residence when i heard a woman from, say, the global north, rudely call a young shop assistant who was dusting the shelves, which caused the bloke to disappear. She sighed loudly and went on a rant about the poor service you got in this damn country. It turned out that the boy had only been concerned about quickly getting help from somebody who spoke English. Seconds later, a smiling saleswoman was inquiring how she could be of assistance, only to be bombarded with a stern lecture from the global north customer on the titles that should be on the books shelves, followed by criticism on the limited offer of books, all of which was so sad, all of which was such a shame.

This anecdote serves, i believe, as a sign that colonisation still exists in the minds of some visitors who appear to be animated by a raging desire to firmly educate and civilise the locals. The world we inhabit may have been revealed to be more complex, more unjust, more unequal and much less certain than used to be considered. These foggy circumstances may feel uncomfortable but they also offer opportunities for betterment, for reparation and restitution (in the national museum in Colombo, a room was dedicated to the presentation of objects that had been restituted by the Netherlands).

I’m not an expert on these topics. I just wish that i could enjoy my ice coffee, my reading or my writing session in an elegant decolonised space without feeling the icy fingers of colonial spectres around my neck.

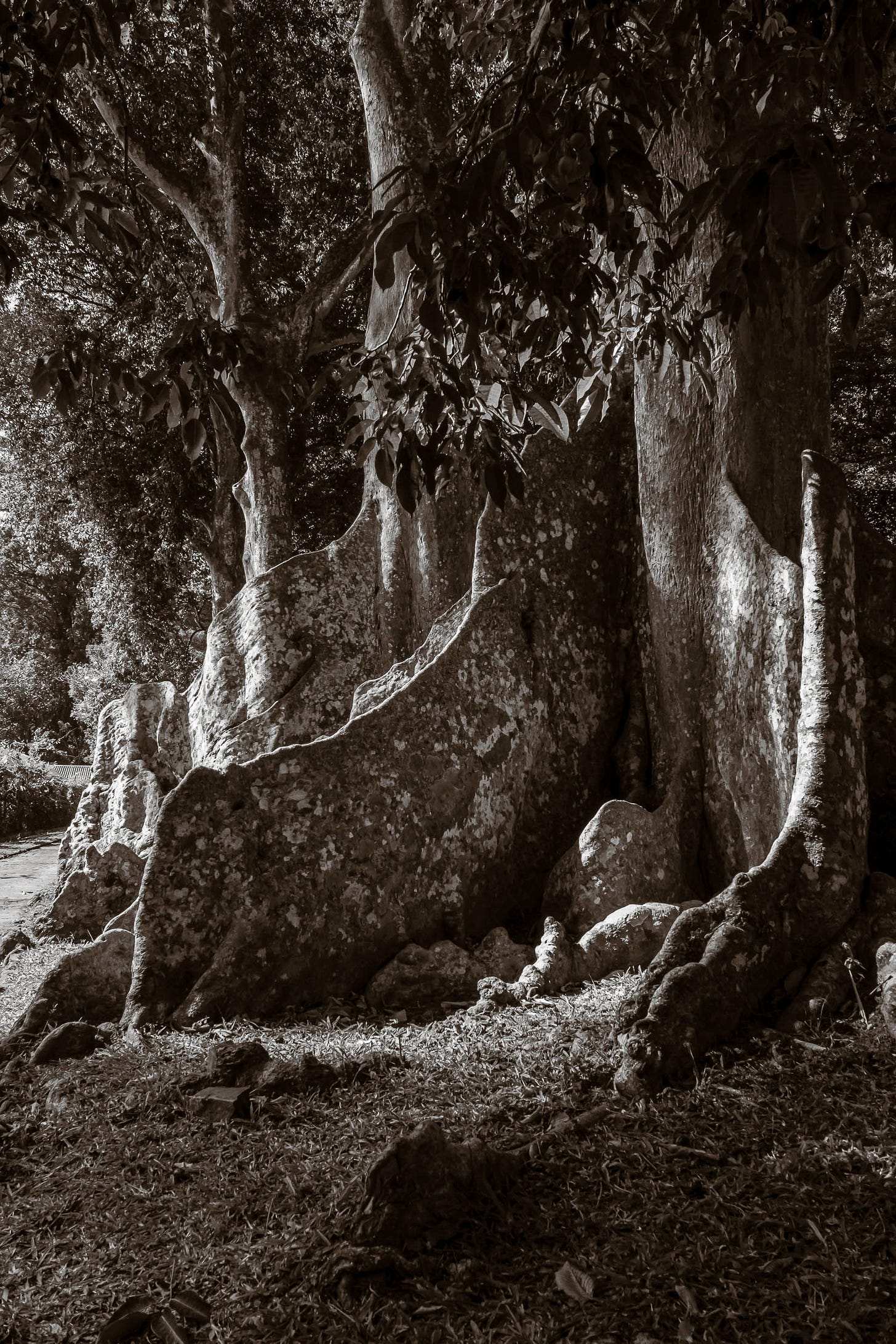

Photos: the roots of canarium trees in the Canarium Row of the Royal Botanical Gardens in Peradeniya (Fujifilm X-T3, XF 16-55 f 2.8, Sri Lanka, 2024).

Thank you for being part of the Tales of Ink and Light.