The woman who was (much more than a) migrant mother

[TIL #23] Looking at the role of photographed persons in the making of images

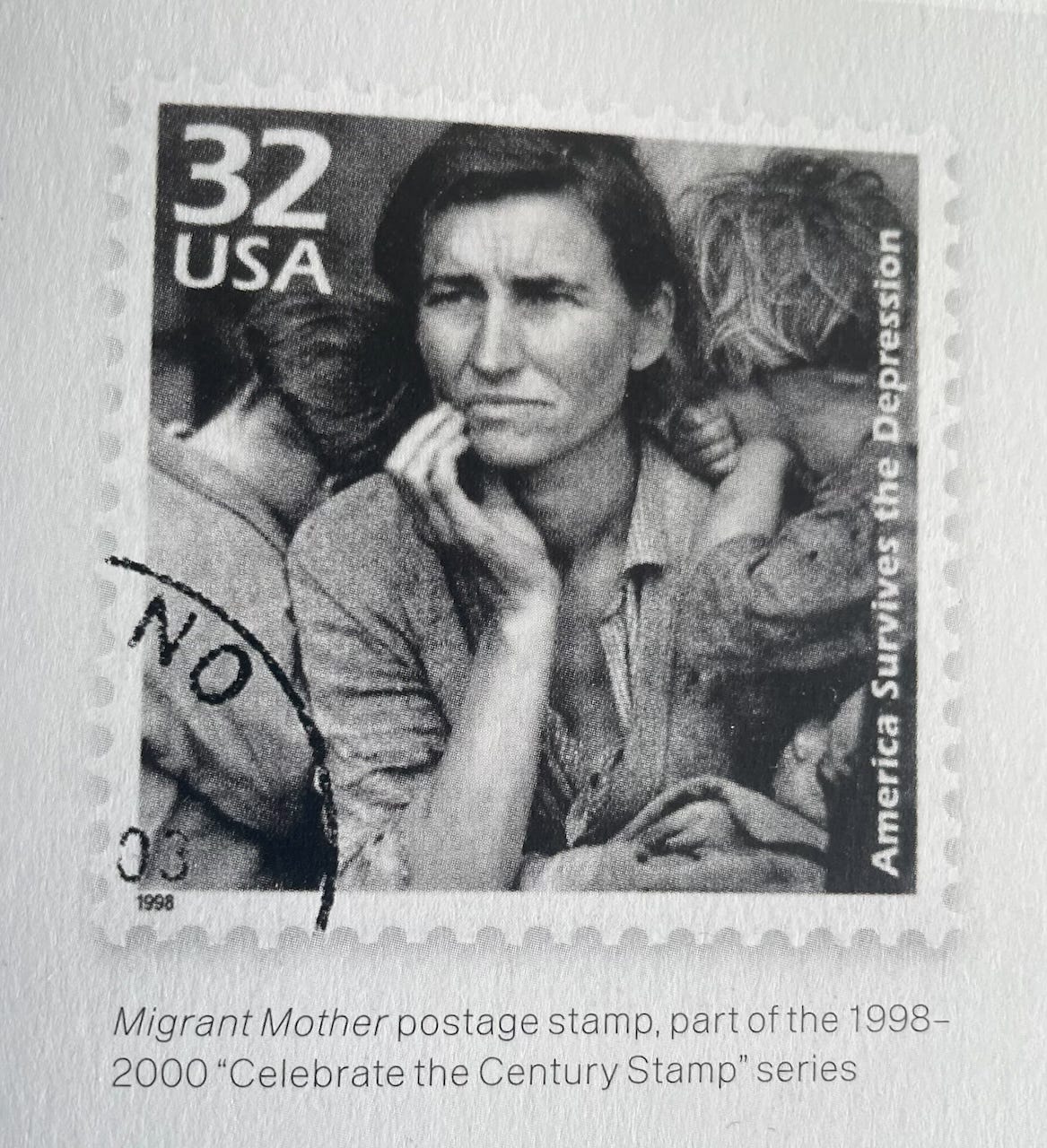

It is a well-known image, a symbol of endurance in the face of harsh circumstances. One evidence of its iconic status is its reproduction on a US stamp in a series about the 20th century. The photograph known as ‘Migrant Mother’ was made in 1936 by Dorothea Lange, who was documenting the living conditions of rural workers thrown on the roads by droughts and a severe economic crisis. The identity of the photographed person remained unknown to the public until the late 1970s, when the woman in the picture told her version of the story and explained that she was ‘tired of being a symbol of human misery.’

This section of the Tales, Touches of Ink and Light, present a journey through the creative process and include stories behind the making of a particular photograph, thoughts and anecdotes on photography and writing, and a look at sources of inspiration.

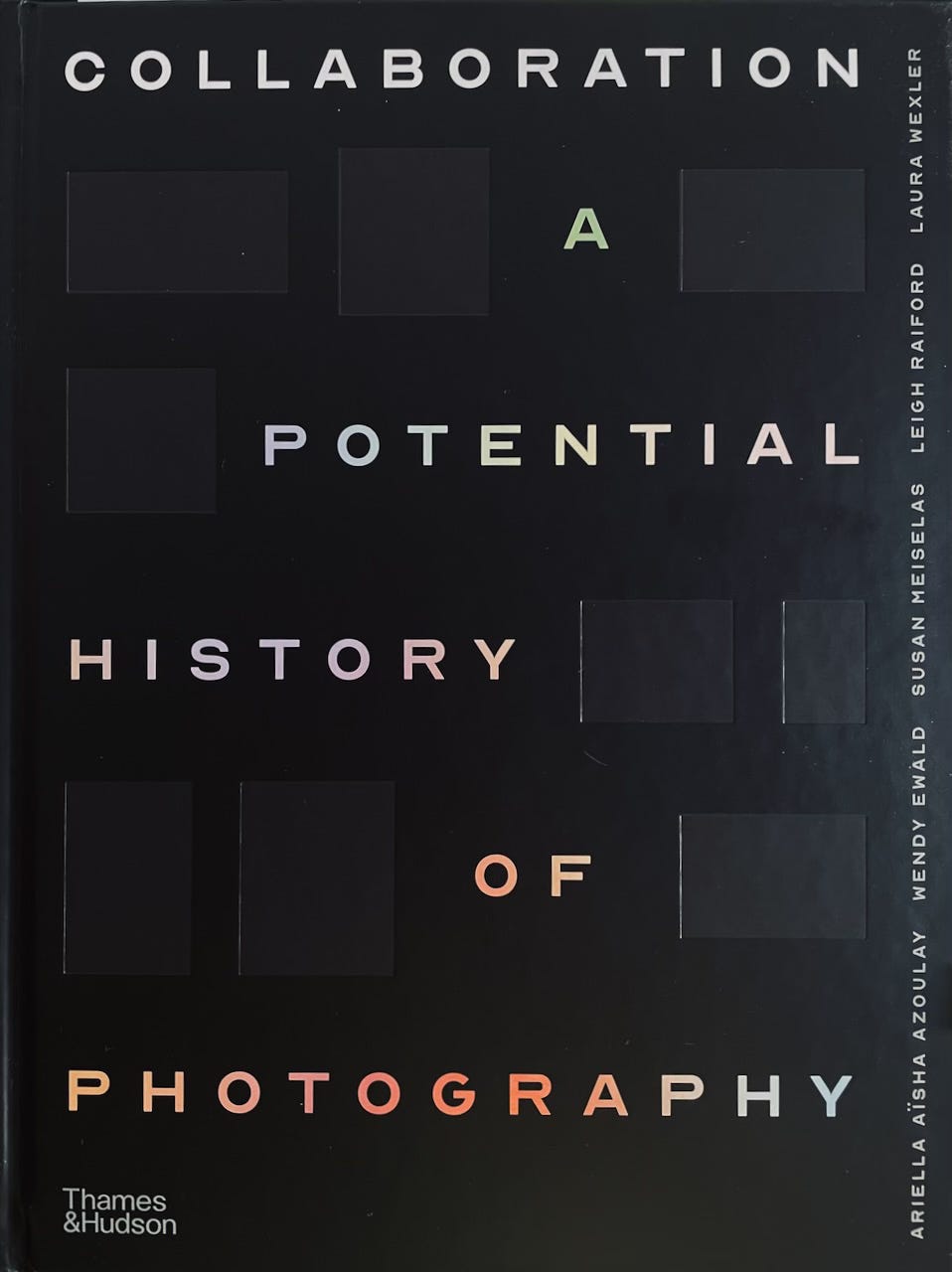

The occasion for me to write about this famous image comes from reading Collaboration - a Potential History of Photography, a publication presented by its authors as ‘an effort to learn from the voices and actions of practitioners, collectives and community members who chose to engage collaboratively with others under different terms than those imposed with violence, negligence or indifference, toward the photographed persons or their world.’1 Conscious that photography has often been an instrument of power and abuse of power, the authors have explored the role of the photographed persons in the making of images.

The book consists of 2-page presentations of photography projects. It is a slow read because it asks deep questions without seeking to provide quick or authoritative answers: what it does, is keep the thinking engine running — and i quite like that. The two pages about the image known as ‘Migrant Mother’ are entitled ‘the exhausted photographed person.’

I remember enjoying my visit of Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, a beautiful exhibition at the Barbican in London and Jeu de Paume in Paris. In the catalogue, David Campany writes that

‘photographs become iconic when they become default substitutes for the complexities of the history, people or circumstances they could never fully articulate but to which they remain connected, however tentatively. As with monuments to almost forgotten battles, they are symbolic placeholders, public markers for a missing comprehension. If any photograph deserves the mixed blessing of being described as 'iconic' it is Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother (1936). It has become one of the most recognised and reproduced, with all the power and problems this entails.’2

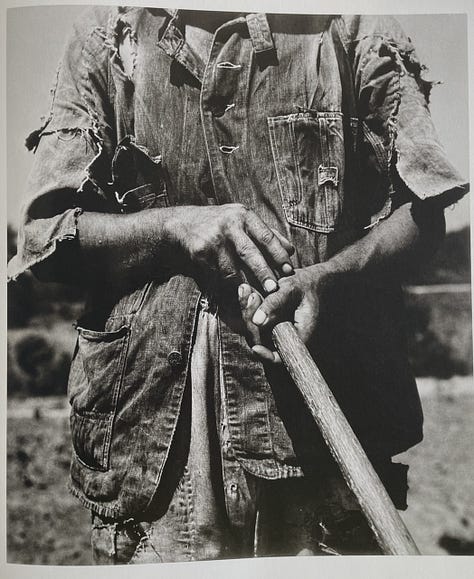

The technical aspects of the picture have been discussed in detail. One often-told fact is the darkening of a thumb on the lower right corner — a famous instance of post-processing in the pre-photoshop era. Everyone agrees that it is a powerful, unforgettable image. What then are the problems with its iconic status?

In 1936, Dorothea Lange was working on assignment for the US Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration (FSA)): she was on a mission to document the living conditions of rural workers thrown into migration by the severe droughts. The administration needed images that could boost public support for the New Deal measures.

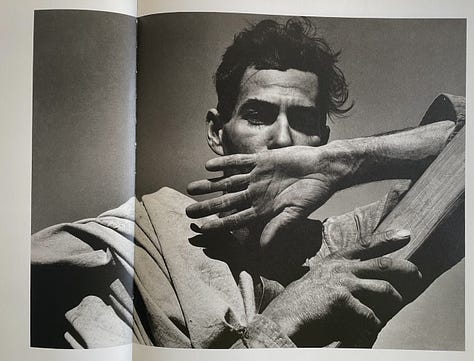

Lange herself was certainly driven by a solid social consciousness. She had left behind her successful studio in San Francisco to document social issues. She would usually spend time speaking with the persons she photographed. She kept notes on these conversations and the photographs she made. In 1939, she co-authored An American Exodus: a Record of Human Erosion with her husband Paul Taylor, a sociologist who also worked for the FSA. In this book, we see her photographs side by side with words of the photographed persons: i find this an effective example of words working with pictures rather than one being a mere illustration or explanation for the other — the quotations sort of insert the voice of the photographed persons into the image.

However, on this particular occasion where she made a short break on the road and shot six images, she kept little written traces of her encounter with the woman who became known as the ‘migrant mother’.

Little after the publication of the photograph, the government shipped food and supplies to the area. The photograph rapidly rose to fame and, although it may not have financially benefited to Lange (as she was an employee of a public administration at the time, the copyright was in the public domain), it certainly contributed to her reputation as a photographer.

In 1960, then a well-known artist, Lange responded to an interview in Popular Photography magazine and described the making of the image as a collaborative process:

’she seemed to know that my pictures could help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it’.

It is only in 1978 that the public heard of Florence Owens Thompson when ‘the woman in the photograph’ expressed her distress at being identified as the face of poverty.

‘I'm tired of being a symbol of human misery; moreover, my living conditions have improved. I didn't get anything out of it. I wish she hadn't taken my picture.... She didn't ask my name. She said she wouldn't sell the pictures. She said she'd send me a copy. She never did.’

There had been factual errors in the caption that accompanied the initial publication of the photograph. Moreover, a key dimension of her identity had not been registered: Florence Owens Thompson was a native American, born from Cherokee parents, and thus heiress to another layer of history of dispossession and forced migration.

Towards the end of her life, after she suffered a stroke, her children launched a call to the public as they were seeking help to face the medical bills. And the public responded not only with considerable amounts of financial support but also with a huge quantity of letters that honoured the ‘migrant mother’ as an inspirational figure of dignity and courage. Seeing that the famous picture of Florence Owens Thompson was more than the face of poverty seemed to have helped the family make their peace with the iconic image. In 1983, on the tombstone of their mother, the children inscribed: ‘Migrant Mother: a Legend of the Strength of American Motherhood.’ (You can learn more about her life in this video.)

I assume most of you are familiar with the ‘migrant mother’, but did you know the story of Florence Owens Thompson?

I found of particular interest to read that already in 1958, in a letter to U.S. Camera magazine, Florence Owens Thompson had asked to be consulted about the future use of her image. The documentation of events of public significance is of key importance in a democratic society, and there is no doubt that Dorothea Lange was driven by a serious concern to understand the persons she photographed and to represent the reality of their lives. But on the other hand, the pain and resentment of Florence Owens Thompson and her family are very legitimate: at the very least, they should be heard and be made an integral part of the story whenever the image is shown (here is the story told by her grandson).

‘When the photographed person resists this iconicity and negotiates the transformation of their lived experience or of their image into an icon, an iconoclastic process has already begun and other potentialities are left alive’.3

As i was browsing through images in the preparation of this text, i was reminded that my mother owned a copy of the French version of the catalogue of the Barbican/Jeu de Paume exhibition. She always was very sensitive to issues of social justice and she loved the ‘migrant mother’, which reminded her of women from her native village and farm workers from her family.

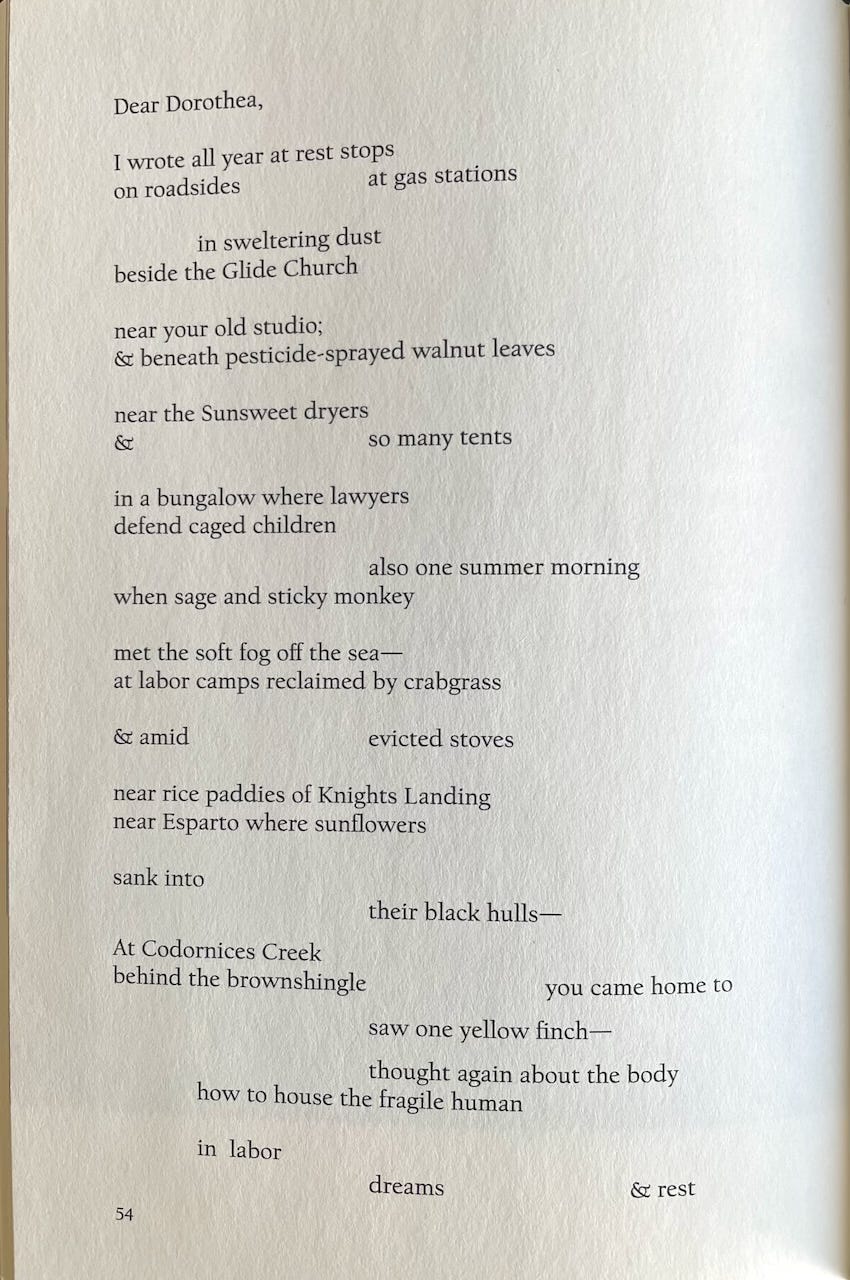

And in a newsletter that is interested in the relationship between texts and images, a fitting conclusion comes from another exhibition of Lange’s work: Words and Pictures at MoMa was the occasion for the publication of a long poem inspired by Dorothea Lange: Last West - Roadsongs for Dorothea Lange, by Tess Taylor, is a moving contemporary documentary road trip on Lange’s tracks.

Thank you for reading the Tales of Ink and Light. It’s good to have you on board.

Collaboration - a potential history of photography, A. Azoulay, W. Ewald, S. Meiselas, L. Raiford, L. Wexler, Thames and Hudson, 2023

David Campany, in Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, Prestel, 2018

From the introduction to the chapter titled ‘Iconization is preceded by collaboration’ in the book Collaboration.

Very interesting essay and commentary here! Thank you, Pierre!

I assume you are both familiar with Patrick Witty here on Substack? His take on iconic war/tragedy images are always insightful. I think one issue to keep in mind always, is that we look at these images with a many-year historical perspective, long after the jury of popular culture/opinion has had its say. The images by now are fully stamped into our consciousness. But as you and William point out, at the time of the actual photograph taking, this was just one of many, many images that would likely get filed away in the archives. Who amongst us photographers has any say in what photos go viral? I mean, we can make the choice NOT to shoot a particular photo for ethical reasons, but once we take the picture and make it public, it's out of our hands, no? How Lange or Ut handled the eventual notoriety is where there is room for serious critique of the photographer's intention. I'm not certain Lange handled it very well, but that's for another essay.